A Historical Guide to

England’s Oldest Public House

Written by Cliff Ivers on behalf of Middleton Archaeological Society

Supported by Edgar Wood and Middleton Townscape Heritage Initiative

May 2017 Version

The Olde Boar’s Head is a rare example of an early timber framed building, acknowledged by Historic England as outstanding, it is Grade II* listed and claims the title of the oldest original public house in England.

Part of the timber framing to the right of the front door has recently been tree-ring dated and confirms a building date of 1622. The first tenant was Isaac Walkden, son of Middleton schoolmaster, Robert Walkden. Isaac died during a typhus epidemic in the summer of 1623. His will, preserved at Lancashire Archives, includes an inventory of all his possessions listed on a room by room basis. There were a total of 9 beds and 20 chairs or stools in the 6 rooms. This, together with barrels, brewing vessels, pots, glasses, etc, strongly suggest the building was an inn. The Walkden family went on to run the Boar’s Head until the end of the 17th century. They also farmed nearby land including what is now Jubilee library and park.

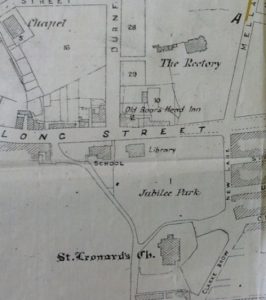

The original building was commissioned by Sir Ralph Assheton, lord of the manor, who handed the lease to the rector of Middleton to help provide him an income. It was built on the road to Rochdale, part of the ancient highwa y between York and Chester. The location is between the rectory and St Leonard’s church on what was known as glebe or church land.

y between York and Chester. The location is between the rectory and St Leonard’s church on what was known as glebe or church land.

The Inn may have been built to accommodate lay visitors to the church or school; early leases describe the building as the Lower House. The title Boar’s Head does not appear in any 17th century documents but may have an association with the heraldic crest of the Assheton family. The first Sir Ralph Assheton was a friend of Richard III whose coat of arms included a white boar. It became known as the Old Boar’s Head in the 1830’s changing to the Olde Boar’s Head in the 20th Century, occasionally prefixed with “Ye”.

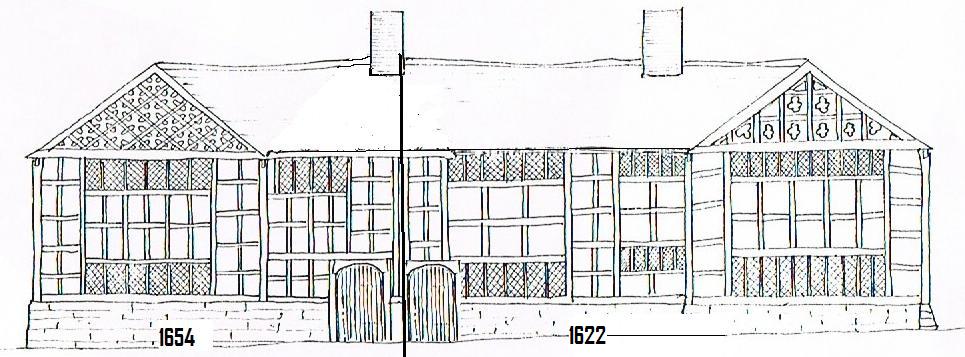

The building was extended to the left (south) in 1654 using identical timber frame construction methods. A brick built assembly or sessions room was added to the right in the 1830’s connecting the pub to existing farm buildings. Later extensions to the rear now contain the kitchen, toilets, Bamford and Fisherman’s room. Cottages to the left of the Inn were demolished by Middleton Corporation in 1892 to make way for Durnford Street. The farm buildings collapsed into the road and were demolished in 1920.

WJ Smith sketch with construction dates added

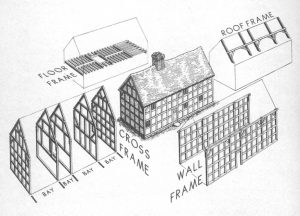

The oak frame, standing on a stone plinth to protect it from the damp ground, consists of 10 wall and 6 cross frames manufactured off site and reassembled during construction. Each joint would be custom fit and carpenter’s assembly marks were added to identify each piece. These marks can still be seen with careful examination. Stone buttresses at ground level support the weight of the main timber post.

The building consists of five bays, three to the right of the front door and two to the left. The oak was felled locally and matches extremely well with the timbers used to build nearby Tonge Hall. The logs would have been split or cut to size very soon after the tree was felled; it was much easier to work with green oak. Once the joints were assembled, the frame was firmly locked together with oak pegs creating a very strong structural shape. The stone roof tiles are graduated with the largest pieces at the base to ensure the frame could take the full weight of the roof. Most of the distortion you see in the frame probably happened within the first few years of use. The timbers are now as hard as steel.

Next, the square panels were each filled with ‘wattle and daub’. You can still see a surviving example of this in the bar area protected by perspex. Vertical oak staves would have been inserted first with a wattle of clefted timber wound between them in a basket fashion. A layer of lime plaster mixed with horse hair was daubed on either side and finished off with lime wash.

Both of the original buildings had a fire hood fitted over an open fireplace. Remnants of these were photographed during the 1980’s renovations. Stone and brick fireplaces were added later when the use of coal was established.

You can see the remains of two bricked up external doors to the left of the front door indicating there was a conversion to three separate houses at one time. The three gablets have a quatrefoil (four leaf) decoration, the one nearest Durnford Street is original and filled with wattle and daub, the middle one is a later addition and the right hand one has been refurbished.

Throughout the 18th and 19th century, the Boar’s Head continued to be a thriving public house. It was used for political, public and church meetings. Entertainment included dialect poetry reading and prize fighting in the barn. Quarterly court sessions were held in the Sessions room where visiting Justices of the Peace from the Salford Hundred helped local magistrates deal with crime.

In 1888, the fledgling Middleton Corporation purchased the building from the church with the intention of demolishing it to build a town hall. Discussions were held in 1914 but, thankfully, the plan was abandoned due to an outcry from the public spearheaded by architect Edgar Wood. The pub was briefly let to the Peoples Refreshment Housing Association in 1902. They had a failed attempt at promoting temperance on the premises.

Middleton Corporation became part of Rochdale Borough Council in 1974 and they leased the pub, firstly to Tudor taverns, then to local brewery J. W. Lees who in 1988 undertook a massive restoration into the fine building we have today.

Tour Guide

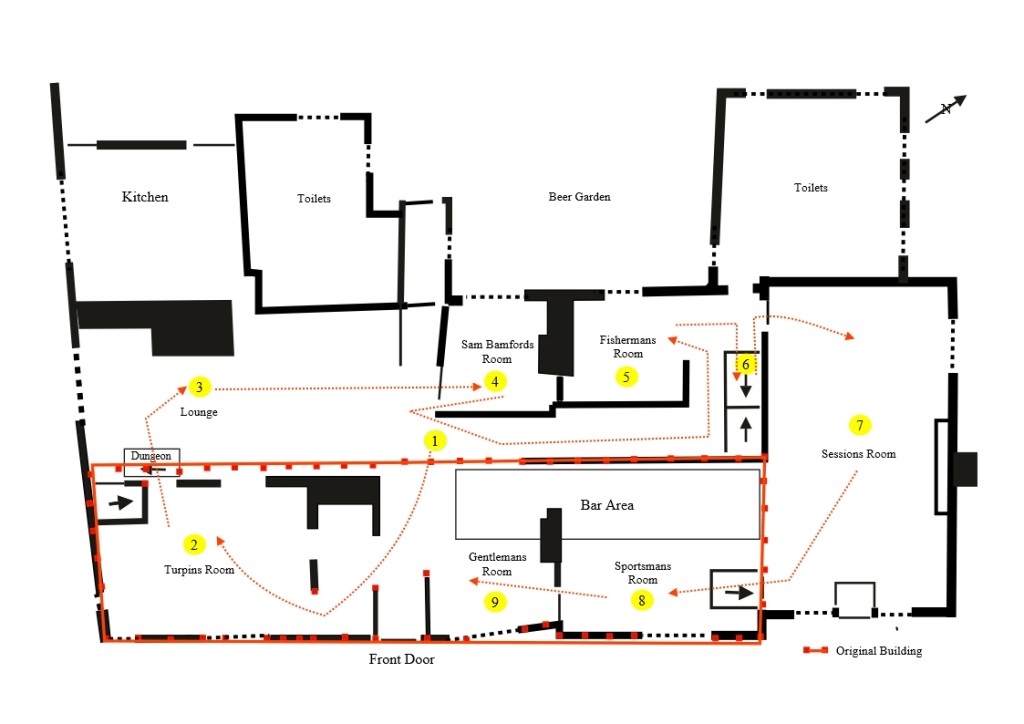

1. Bar Area

You are standing at the rear of the original building. Look up towards the old pub sign and you can see what used to be a bedroom window. A surviving example of the wattle and daub is behind the perspex.

The large photograph is dated about 1880; the blurred figure at the door is either Sam Bamford’s ghost or, perhaps a local who nipped in for a pint whilst the photograph was taken on long exposure!

Behind the photograph, there is a boarded-up door which was probably the back door to the original buildings. The metal window is rumoured to be a cell that held prisoners awaiting trial in the Sessions room

2. Turpin’s Room

Head towards the front door and turn right into Turpin’s Room- but MIND YOUR HEAD! Dick Turpin, an Essex butcher turned highway robber, was hanged at York in 1739 for horse theft. He was made famous in a Victorian novel and this later notoriety led to many local myths, particularly relating to him and his horse, Black Bess, visiting local Inns.

Look at the hefty beam in front of you, it dates back to 1565 and may have been part of an earlier building. It is part of the original inglenook fireplace and known as a bressummer (it supports other beams). The wall behind the fruit machine conceals a bricked-up door to this part of the building. Baffle screens on either side of the now lost fireplace blocked the draft and held seats inside the inglenook. Originally, the fire would have burned directly on the floor and a smoke hood would have funnelled smoke up through the roof. As coal replaced timber as fuel, brick chimneys and fire ranges were added.

The wall painting is of Tonge Hall. Built in 1582, its remains are still on William Street awaiting renovation after a fire. It has many similarities to the Boar’s Head and you can see the use of black and white quatrefoil styling on both buildings.

3. Lounge

As you enter the lounge, notice the staircase with its large Jacobean acorn style newel post made from a Baltic hardwood. It was most probably reclaimed from another building. The stairs have been crudely supported with an old cruck blade on the left, again most probably recycled from another Middleton building. Cruck blades were naturally curved pieces of timber used to support a different style of construction to the box frame of this pub. During refurbishment in the 1980’s a child’s shoe was discovered hidden behind the stairs where it still remains today.

The trap door in the floor leads to what has been christened ‘The Dungeon’. This cellar has a stone flagged floor and walls running under the Turpin Room to the front wall. It used to have window lights opening onto the pavement, framed with stone mullions. There was also an opening or coal chute leading under the pavement which conjured up stories of a secret tunnel to the church.

4. Sam Bamford Room

Sam (1788-1872) was a famous local writer and radical thinker who led a band of neighbours to a parliamentary reform demonstration in 1819 that became known as the Peterloo massacre.

Sam often frequented the Boar’s Head where he held meetings and recitations of his poems in local dialect. We recommend his book ‘Early Days’ (1849) where he writes of his father Daniel fighting at the Boar’s Head in the ‘Thrashing Room’ (Barn). The fight lasted two hours and ended with Daniel’s powerful opponent being carried away by his supporters.

Again, referring to the turbulent times of the eighteenth century, Bamford described how his grandfather Jeffery Battersby joined the ‘Pretender’s Party’ at the Boar’s Head. The Pretender was ‘Bonnie’ Prince Charles Stuart who laid claim to the English throne. Battersby used his local knowledge to help collect the ‘King’s’ Taxes in other words contributions from local people.

Despite Stuart’s Scottish army getting as far south as Derby, the Jacobite rebellion failed in 1745. Sam’s grandfather was arrested for treason but was fortuitously released from Lancaster Gaol and continued his trade as a cobbler.

5. Fisherman’s Room

This room is dedicated to Middleton Angling Society which was formed in 1845 and used to meet at the Kings Arms pub until about 1934 when they moved to the Boar’s Head. The specimen brown trout was caught by C Jackson at Chadwick and Smith’s works in 1924 and weighs 2lbs 5¾ ozs. The roach next to it was caught by club president, T Howarth, in the same year and weighs in at 1lb 4 ¾ ozs. The picture “Anglers Companion” was given to the society in 1923 by Mrs Wellens of the Kings Arms Pub. The Society is still in existence and fishes at Baguley Brow reservoir.

6. Meeting Room

Ignore the door to the north cellar which is mostly of modern construction and climb the north stairs. These stairs were partially refurbished in 1983 to match the Jacobean style of the other staircase. The Meeting Room is the best preserved room in the building. The door is of fine quality and has been reinforced; you can see carpenter’s marks on each piece. The glazing is not original but holes in the bottom sill show where the first glazing bars were fitted. The wooden mullions contain a number of deliberate burn marks.  These were made with a lit taper either to ward off evil spirits or to guard the building from lightning strikes or fires. Literally fighting fire with fire!

These were made with a lit taper either to ward off evil spirits or to guard the building from lightning strikes or fires. Literally fighting fire with fire!

The corners of the room have diagonal wind braces to help keep the roof frame attached and give structural strength to the building. The floor has a reassuring creak of authenticity.

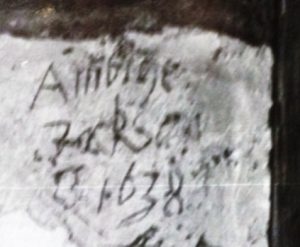

The fireplace wall contains rare remnants of early 17th Century decorative wall paintings that were discovered in 1993 and later recorded by Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit. They also discovered graffiti in the form of names scratched into the plaster. If you look near the ceiling just to the left of the fireplace, you will see the signature of a local man, Ambrose Jackson dated 1638. Other names scratched on the wall include Robert Clough, John Howarth, Robert Boultons, Francis Cheetham and John Scourcroft. A second date of 1642 is linked with Boulton’s name.

7. Session’s Room

Returning downstairs, you need to turn right into the Sessions Room. In the 18th Century, this may have been the Thrashing Room, used for prize fights. (see the Sam Bamford Room)

It was later adapted to a court room used for administering justice when Middleton was part of the ancient Salford Hundred. Regular court sessions were held in each Hundred township by visiting or local magistrates. The Old Boar’s Head was known to be the home of the local sessions court from 1836 to 1852. Cases ranged from minor licensing or property disputes to petty theft and common assault. The outside of the room suggest three different building phases for this part of the building. It may have been a stable or courtyard entrance in the 17th Century whilst the Venetian or Palladian style door in the room is late Georgian. The room was probably converted to an assembly room at the end of the 19th century, used for meetings and public auctions.

The grand stone fireplace in the room bears the date 1587 and the Boar’s Head symbol which was the crest of the Assheton coat of arms, the Asshetons being lords of Middleton. The fireplace was located in Middleton Hall and moved here after the Hall was demolished in 1845.

The 20th Century saw the room being applied to many uses including cocktail bar, discotheque and pool room. It currently holds private functions and is used by Slimming World, MAS and the Civic Society.

8. Sportsman’s Room

Going into the Sportsman’s room you can clearly see the construction of the box frame with the wattle and daub removed. Bridging beams support the ceiling and are the most substantial pieces of timber in the building. However, the brackets that hold them look rather primitive. The front of the building tilts towards the main road as does the sign, all adding to the charm of the place. The window frame looks modern and is much taller than the original frames. This would have been the main parlour in the 17th century.

9. Gentleman’s Room

The wall between the Sportsman’s room and the Gentleman’s room is topped by another bressummer. The remains of the inglenook fireplace were removed when it was replaced with a brick chimney stack. The internal door was added in 1999. Originally this area would have contained the kitchen with the area behind the bar being the brew house.

The Olde Boar’s Head with the Sessions Room and farm building to the right and the cottages, demolished in 1892, still across the mouth of what is now Durnford St. The lower (third) door can be seen near the ladder. The photograph predates Long St Methodist Church by some thirty years and Jubilee Park is still part of the farm.

Tenants of the Boar’s Head, Middleton

|

Isaac Walkden |

1622-1623 | Henry Shuttleworth | 1835-1875 |

| John Cheetham | 1623-1634 | John Jackson | 1875-1876 |

| Benjamin Walkden | 1634-1642 | Alfred Wood | 1876-1898 |

| John Taylor | 1642-1657 | Eliza Wood | 1898-1902 |

| Isaac Walkden | 1657-1669 | George Stone | 1902-1904 |

| Grace Walkden | 1669-1684 | G R Mends | 1904-1907 |

| Benjamin Walkden | 1684-1700 | Robert Williamson | 1907-1909 |

| John Taylor | 1700-1713 | Eric F Godsell | 1909-1911 |

| James Ridings | 1713-1737 | Samuel Bromley | 1911-1917 |

| Edmund Hopwood | 1737-1750 | Arthur Hough | 1917-1934 |

| Joseph Lancashire | 1750-1751 | Alfred Walker | 1934-1940 |

| Josiah Fitton | 1751-1752 | Annie Walker | 1940-1945 |

| Mary Fitton | 1752-1766 | J A Motler | 1945-1950 |

| Joseph Holebrook | 1766-1770 | Chris. Crossland | 1950-1962 |

| Alex. Cheetham | 1770-1773 | Patrick Hannelly | 1962-1980 |

| Peter Travis | 1773-1780 | Brian Inger | 1980-1982 |

| Mary Cheetham | 1780-1783 | Arthur Radcliffe | 1982-1986 |

| Robert Caley | 1783-1798 | Leslie Hardman |

1986-1989 |

| James Warburton | 1798-1802 | Martin Reeves | 1989-1995 |

| Mr Wardle | 1802-1803 | Mrs M Sharkey | 1995-1999 |

| Mr Lourdes | 1803-1805 | Mr G Norton | 1999-1999 |

| John Goodwin | 1805-1823 | Mr S Brennan | 1999-2003 |

| George Baines | 1823-1824 | Mr & Mrs T Way | 2003-2006 |

| Simon Isherwood | 1824-1825 | Mr G Mervin | 2006-2006 |

| William Moult | 1825-1833 | Claire Robinson | 2006-2009 |

| James Ogden | 1833-1835 | Leanne Brogden | 2009- |

Middleton Archaeological Society (Charity ref XT 36464) welcomes donations to support its activities. www.middletonas.com

Information was researched by the author at both Manchester and Lancashire archives, Middleton Library, J W Lees and using “Middleton Pubs 1737-1993 and their licensees, Rob Magee, Richardson 1993” Kindly edited by local historian Geoff Wellens.

© 2017 Middleton Archaeological Society.

© 2015 cover sketch by Steve Whitworth